J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 19(1):46-56.

doi: 10.34172/joddd.025.41487

Original Article

A randomized clinical trial on innovative functional esthetic appliance for craniofacial growth modulation with 3D analysis of TMJ

Shubhangi Mani Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing,

Nandlal Girijalal Toshniwal Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing,

Yash Goenka Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing,

Nikita Navgire Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, *

Ankita Khurdal Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing,

Author information:

Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Rural Dental College, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences (DU), Loni, Maharashtra, India

Abstract

Background.

The present study evaluated condylar position changes using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in treating Cl II malocclusion with the twin block and clear functional jaw corrector (CFJC) appliances.

Methods.

In this RCT, we included 60 patients, with 30 in each treatment group (control group: twin block appliance, case group: CFJC appliance), randomly allocated using a lottery system. A twin block appliance or CFJC was fabricated for each patient following the protocol. Pre- and post-treatment records were collected over twelve months at 0-, 6- and 12-month intervals using cephalograms, CBCT, and questionnaires assessing the patient perception of the appliance.

Results.

Both groups showed significant improvements in malocclusion. Cephalometric analysis showed statistically significant differences between the two groups in SNB, ANB, and U1-NA. In comparing the two groups, significant differences were found in Arnett’s soft tissue parameters, including upper lip to E line, lower lip to E line, upper lip protrusion, upper lip length, lower lip length, lower 1/3 of the face, maxillary first incisor exposure, and mandibular height in the CFJC group. The intergroup comparison of projections to TVL (true vertical line) also showed significant differences across all parameters in the CFJC group. Furthermore, significant disparities in CBCT parameters were observed between the groups, specifically in condylar position, condylar height, and anterior joint space. Also, significant differences in patient comfort and perception of the appliance were observed, highlighting better compliance with the CFJC appliance.

Conclusion.

The CFJC appliance is a top choice for Cl II malocclusion due to its superior effectiveness in skeletal, dental, and soft tissue improvements and significant condylar remodeling. Additionally, patients showed better compliance and acceptance of the CFJC appliance compared to traditional options, enhancing its clinical advantage in orthodontic practice.

Keywords: Cl II malocclusion, Clear functional jaw corrector, Dental changes, Skeletal changes, Twin block appliance

Copyright and License Information

© 2025 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

None.

Introduction

The orofacial region is vital for interpersonal interactions and communication. Malocclusion, a deviation from normal tooth alignment, often requires orthodontic treatment to achieve optimal occlusion, balancing function, stability, and aesthetics. Cl II malocclusion, affecting about one-third of the population, is typically characterized by mandibular skeletal retrusion and can impact respiratory function and sleep. ‘Airway friendly orthodontics’ involves functional therapy to enhance mandibular growth.1 Various removable functional appliances, such as the activator, bionator, Frankel, and twin block, are used to correct Cl II disharmony. The twin block, developed by William J. Clark, is particularly popular for its effective, speech-friendly design.

Understanding the twin block mechanism is crucial for orthodontists. This appliance primarily induces sagittal changes, increasing mandibular length and improving the facial profile from convex to straight. It enhances the anteroposterior diameter and condyle height, repositions the condyle forward, and causes backward disk movement. Modifications in the glenoid fossa due to tissue stretch and altered synovium flow result in significant bone formation within six months. These changes, influenced by viscoelastic tissues, occur alongside skeletal, dental, neuromuscular, and age factors. However, functional appliances can cause discomfort, including mucosal pressure, soft tissue tension, and speech difficulties, impacting patient compliance.2 Orthodontists must select suitable appliances and manage discomfort effectively.

Patient compliance significantly influences the success of removable orthodontic appliances.3 O’Brien et al5 noted that non-compliance often hampers early twin block treatment.4 The bulkiness and visible wires of traditional appliances contribute to non-compliance. Newer, more comfortable, and lightweight wireless appliances are needed. Though effective with better compliance, the fixed twin block can cause gingival inflammation, food lodgment, foul odor, and discomfort.6 Clear aligners, offering better esthetics and comfort, show promise. They reduce gag reflexes and improve patient satisfaction. The “clear twin block” developed by Behroozian and Klaman retains traditional benefits while enhancing comfort and esthetics by eliminating wire elements, increasing patient compliance and treatment efficacy.7 Recently, there has been a transition from traditional braces to transparent tooth positioners or aligners for treating mild to severe crowding and extraction cases. As a result of the growing demand for esthetic solutions, the clear mandibular advancement appliance was developed. This appliance combines features of both a functional appliance and an aligner, offering an alternative treatment option.8

Many studies have evaluated the skeletal outcome of twin-block treatment with mixed findings. Some reports have shown significant mandibular growth,9 while others note primarily dentoalveolar changes.10 Duan et al11 found that twin-block appliances effectively reduced pediatric OSA symptoms. Mandibular growth is linked to temporomandibular joint (TMJ) responses, and studies using CBCT have shown forward condylar positioning and remodeling.12 Effective TMJ changes involve condylar changes, glenoid fossa remodeling, and condylar displacement. There is a lack of studies with larger sample sizes, comprehensive evaluations of skeletal, soft tissue, and TMJ changes, along with compliance factors.13-18 Therefore, we conducted this study to obtain more conclusive results.

Methods

Fabrication of prototype

Thermoformed vacuum clear “copyplast” material of various thicknesses was used to fabricate prototypes for the clear functional jaw corrector (CFJC). Acrylic blocks with various mechanical adhesive mechanisms were incorporated into these prototypes. After testing different thicknesses, a 1-mm thickness of the clear thermoformed sheets was chosen for its durability and ability to withstand mechanical forces. Small grooves along the sides of the acrylic blocks were added, which proved effective in retaining the blocks securely within the CFJC appliance. This design ensured both functionality and durability, making it suitable for clinical use.

Clinical study

The present experimental study was performed in 2 years (May 2, 2022, to April 30, 2024) with an observational period of one year. The study was approved by IEC and conducted in the Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics Division, Rural Dental College, Loni.

Outpatients from the department were selected based on eligibility criteria. The total sample included 60 subjects determined using Dr. Kulkarni’s software comprising both sexes randomly divided into two groups by lottery method:

T: The test group using a CFJC

C: The control group using a twin block

Inclusion criteria

simple

-

(i) Age group of 12‒16 years with CVMI stage 3‒4 and MP3 stage F to FG eligible for myofunctional therapy

-

(ii) Skeletal Class II with orthognathic maxilla and retrognathic mandible (Salzmann Class II type 2) eligible for myofunctional therapy

-

(iii) Angles Class II div 1 malocclusion with increased overjet and overbite eligible for myofunctional therapy

-

(iv) Patients with early permanent dentition eligible for myofunctional therapy

-

(v) Patients with well-aligned dental arches eligible for myofunctional therapy

-

(vi) Patients ready to give written informed consent and participate in the clinical trial, who were eligible for myofunctional therapy

Exclusion criteria

simple

-

(i) Patients with numerous local/systemic problems/syndromes or traumas that influence the growth and development of facial structures or body

-

(ii) Patients with a history of orthodontic or interceptive treatment

-

(iii) Patients with facial asymmetry

-

(iv) Patients with mixed dentition or missing teeth

CBCT was taken from the right TMJ region to minimize radiation exposure and standardize the method. The CBCT was taken with a limited field of view.

CBCT imaging protocol

Figure 1 depicts the CBCT images and variables to be studied. Images were taken at 120 kV, 15 mA, and with an exposure time of 10 seconds using a CBCT machine (3D Rainbow). With the patient standing without an interocclusal separator, they were directed to keep their teeth in maximum intercuspation and refrain from swallowing or making other movements during the scanning period. The exposure setting was 110 Kv, 4 mA, 18*16 seconds scanning time. The data were in DICOM format. These data sets were uploaded into rainbowTM CT software funded and sold by Dentium, South Korea, for anatomic landmark localization and TMJ measurements. All the landmarks were located on the sagittal view of the midline plane, aiming to replicate the standard procedure used in lateral cephalograms. Their positions were verified across all orthogonal planes. Rainbow software was used to assess the TMJ and its surrounding space.

Figure 1.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images showing the right condyle

.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images showing the right condyle

The following steps were undertaken during the study:

-

Collection of diagnostic records along with pre-treatment CBCT scan

-

Analysis of diagnostic records and confirmation of skeletal Class II bases with mandibular retrognathia

-

Bite registration protocol

-

Fabrication and delivery of the appliances

-

Check-up of the patients during the period of study

-

Collection and analysis of post-treatment records

-

Extraction of DICOM files from the CBCT scans and importing them to a third-party software rainbowTM CT for the TMJ measurements of the right-side condyle

-

Comparison of TMJ measurements before and after treatment

-

The parameters were recorded at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months by observing clinical variables, cephalometric variables, Arnett’s dentoskeletal factors, Arnett’s soft tissue structure, facial length, projection to true vertical line (TVL), and CBCT variables.

Methodology in the test group (CFJC)

Fabrication

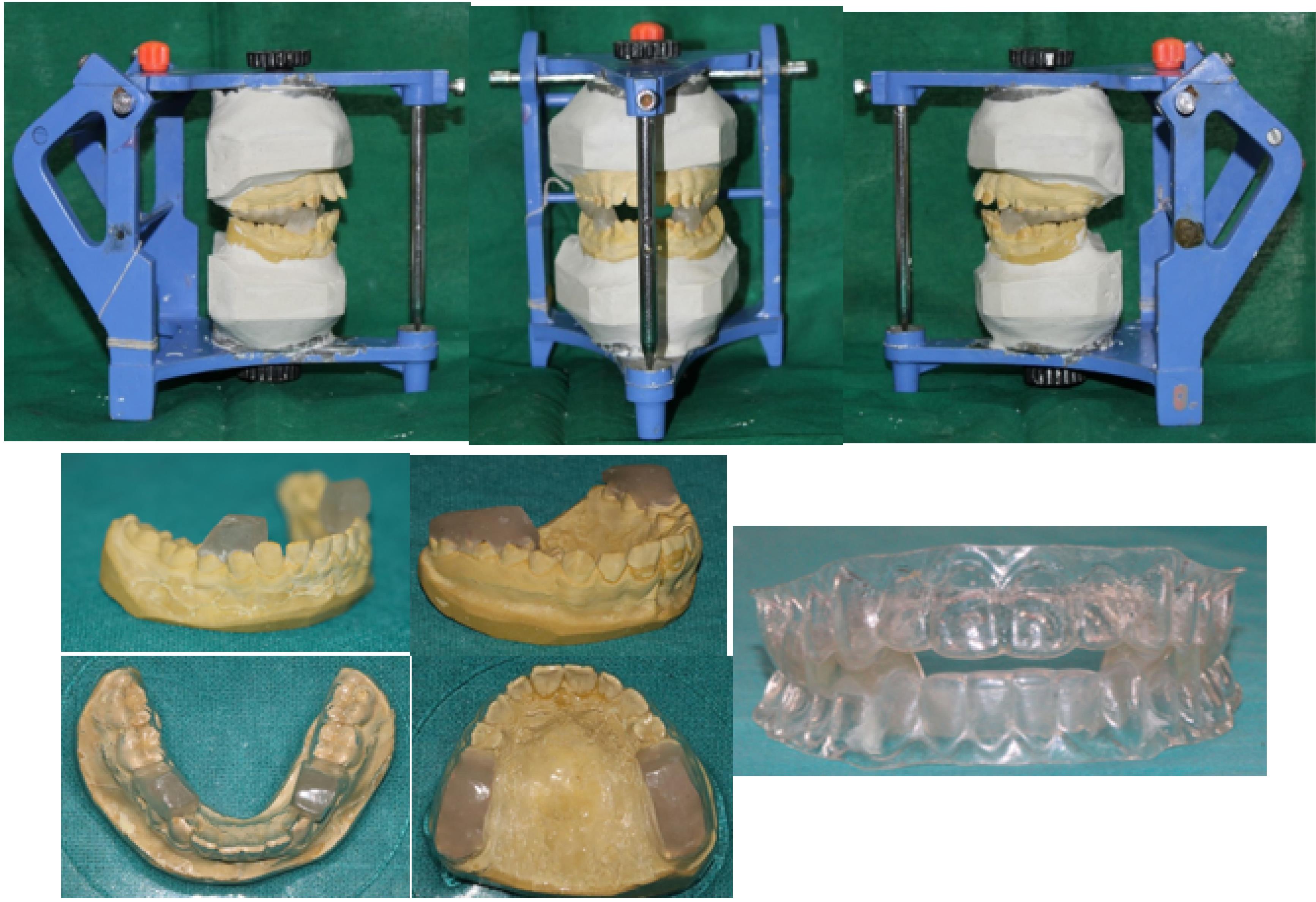

Models were mounted on an articulator with the construction bite in place. The upper bite block was angled from the mesial surface of the upper second premolar and positioned flatly over the remaining posterior teeth. The lower block was angled from the mesial surface of the lower first premolar, extending mesially to cover the premolar and, if necessary, merging into the lower incisal capping area. The inclined plane was angled at 70º to apply more horizontal force components, promoting horizontal mandibular growth. The excess thickness of each block (0.5 mm) was trimmed to accommodate the copyplast sheet. Each block was fixed to the respective cast, and a vacuum-formed procedure was carried out to fabricate the appliance. Figure 2 depicts the fabrication of the CFJC appliance.

Figure 2.

Clear functional jaw corrector appliance fabrication

.

Clear functional jaw corrector appliance fabrication

Figure 3 depicts the preoperative extraoral and intraoral status of patients.

Figure 3.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral pre-treatment photographs of clear functional jaw corrector appliance (CFJC) (the test group)

.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral pre-treatment photographs of clear functional jaw corrector appliance (CFJC) (the test group)

Patient instructions on wear and care were provided, with a follow-up of 2 weeks for pterygoid response. Subsequent recalls at 6 weeks addressed any appliance repairs. Patients were advised to wear the appliance continuously and follow the instructions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Patient’s intraoral photographs with clear functional jaw corrector (CFJC) appliance (the test group)

.

Patient’s intraoral photographs with clear functional jaw corrector (CFJC) appliance (the test group)

The post-treatment extraoral and intraoral photographs of the patients are depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral post-treatment photographs of clear functional jaw corrector (CFJC) appliance (the test group)

.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral post-treatment photographs of clear functional jaw corrector (CFJC) appliance (the test group)

Methodology in control group (twin block appliance)

Figure 6 depicts the preoperative extraoral and intraoral status of patients (control group). Patient instructions on wear and care were provided, with a follow-up of 2 weeks for discomfort assessment. Subsequent recalls at 6 weeks addressed any appliance repairs. The patients were advised to wear the appliance continuously (Figure 7), including during meals, starting with a soft diet and transitioning to normal eating gradually to adjust comfortably. The post-treatment extraoral and intraoral photographs of the patients (control group) are depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 6.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral pre-treatment photographs of twin block appliance (the control group)

.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral pre-treatment photographs of twin block appliance (the control group)

Figure 7.

Patient’s intraoral photographs with twin block appliance (the control group)

.

Patient’s intraoral photographs with twin block appliance (the control group)

Figure 8.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral post-treatment photographs of twin block appliance (the control group)

.

Patient’s intraoral and extraoral post-treatment photographs of twin block appliance (the control group)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA). The unpaired t-test (for intergroup comparison) was used to compare quantitative data of all variables included in the study.

Results

The present study revealed the following outcomes when the results were compared with the baseline data between the two groups. According to Table 1, when cephalometric parameters between twin block and CFJC were compared, statistically significant differences were observed for angular measurements of SNB, ANB, and U1-NA. In contrast, the rest of the parameters did not show statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in the CFJC group. Comparison of Arnett’s soft tissue parameters (Table 2) between the two groups showed significant differences in the upper lip to E-line, lower lip to E-line, upper lip protrusion, upper lip length, lower lip length, lower third of the face, maxillary exposure, and mandibular height. Additionally, notable differences were observed in the intergroup comparison of projections to TVL across all parameters.

Table 1.

Intergroup comparison of cephalometric parameters between twin block and CFJC group

|

Parameter

|

Group

|

Mean

|

Std. Deviation

|

t

-value

|

P

value

|

| SNA (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

-0.2000 |

0.76519 |

1.832 |

0.072 |

| CFJC |

-0.5200 |

0.57440 |

| SNB (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

1.2900 |

1.06717 |

-3.024 |

0.004 |

| CFJC |

2.9500 |

2.81103 |

| ANB (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

-1.5900 |

1.26691 |

3.186 |

0.002 |

| CFJC |

-3.4133 |

2.86714 |

| Saddle angle (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

-1.2667 |

0.46855 |

-1.633 |

0.108 |

| CFJC |

-1.1000 |

0.30513 |

| Articular angle (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

3.3067 |

2.56769 |

0.962 |

0.340 |

| CFJC |

2.7333 |

2.01603 |

| Gonial angle (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

2.1167 |

1.80021 |

0.177 |

0.860 |

| CFJC |

2.0300 |

1.98705 |

| Y axis (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

1.2567 |

0.94638 |

0.477 |

0.635 |

| CFJC |

1.1133 |

1.34773 |

| (Go-Gn)-SN (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

2.3000 |

1.20258 |

-.085 |

0.933 |

| CFJC |

2.3300 |

1.51365 |

| U1-NA (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

-1.4167 |

1.09987 |

-4.136 |

0.000 |

| CFJC |

-0.3300 |

0.92779 |

| L1-NB (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

0.8167 |

1.69423 |

0.475 |

0.636 |

| CFJC |

0.6100 |

1.67422 |

| IMPA (º) |

TWIN BLOCK |

3.0000 |

3.37843 |

-0.297 |

0.768 |

| CFJC |

3.8167 |

14.67727 |

| N perp pt A (mm) |

TWIN BLOCK |

0.2433 |

0.68515 |

1.421 |

0.161 |

| CFJC |

0.0300 |

0.45421 |

| N perp Pog (mm) |

TWIN BLOCK |

2.0033 |

0.81811 |

-1.220 |

0.227 |

| CFJC |

2.4900 |

2.02610 |

| LAFH (mm) |

TWIN BLOCK |

2.9367 |

2.07605 |

0.607 |

0.546 |

| CFJC |

2.6533 |

1.49406 |

| Maxillary unit (Co-pt A) (mm) |

TWIN BLOCK |

0.1867 |

1.46940 |

1.072 |

0.288 |

| CFJC |

-0.3167 |

2.11041 |

| Mandibular unit (Co- Gn) (mm) |

TWIN BLOCK |

3.9967 |

2.50688 |

0.702 |

0.486 |

| CFJC |

3.5700 |

2.19139 |

Table 2.

Intergroup comparison of soft tissue parameters between twin block and CFJC group

|

Parameter

|

Group

|

Mean

|

Std. Deviation

|

t

-value

|

P

-value

|

| U lip to E line (mm) |

Twin block |

0.02 |

0.40887 |

-3.089 |

0.003 |

| CFJC |

0.51 |

0.7667 |

| L lip to E line (mm) |

Twin block |

1.6233 |

0.65794 |

-4.58 |

0 |

| CFJC |

2.5533 |

0.89663 |

| Upper Lip Protrusion (mm) |

Twin block |

-2.4167 |

2.26473 |

-6.427 |

0 |

| CFJC |

0.4733 |

0.96844 |

| Lower Lip Protrusion (mm) |

Twin block |

0.8933 |

9.06064 |

0.422 |

0.674 |

| CFJC |

0.1933 |

0.56013 |

| Nasolabial Angle (º) |

Twin block |

3.7533 |

2.64324 |

-0.968 |

0.337 |

| CFJC |

4.35 |

2.10152 |

| Nasion’-Menton’ (mm) |

Twin block |

2.4767 |

2.06158 |

0.428 |

0.67 |

| CFJC |

2.3 |

0.92476 |

| Upper lip length (mm) |

Twin block |

-0.2633 |

1.51236 |

-4.956 |

0 |

| CFJC |

1.5333 |

1.28636 |

| Interlabial gap (mm) |

Twin block |

-1.1033 |

0.68606 |

-0.707 |

0.483 |

| CFJC |

-0.0867 |

7.8504 |

| Lower lip length (mm) |

Twin block |

1.64 |

2.75663 |

2.465 |

0.017 |

| CFJC |

0.1167 |

1.96383 |

| Lower 1/3 of face (mm) |

Twin block |

0.94 |

1.87683 |

-2.704 |

0.009 |

| CFJC |

1.9667 |

0.89533 |

| Mx1 exposure (mm) |

Twin block |

0.57 |

0.75208 |

3.939 |

0 |

| CFJC |

-0.0033 |

0.26455 |

| Mandibular height (mm) |

Twin block |

-0.9 |

0.96311 |

-3.375 |

0.001 |

| CFJC |

-0.15 |

0.74452 |

| Upper molar to PTV (mm) |

Twin block |

0.6767 |

19.0451 |

0.538 |

0.592 |

| CFJC |

-1.21 |

2.39602 |

| Point A |

Twin block |

0.4 |

0.99516 |

2.93 |

0.005 |

| CFJC |

-0.2067 |

0.54389 |

| Mx1 |

Twin block |

-1.3083 |

0.6114 |

-8.053 |

0 |

| CFJC |

-0.17 |

0.475 |

| Md1 |

Twin block |

1.9933 |

1.73582 |

4.038 |

0 |

| CFJC |

0.4667 |

1.12903 |

| Point B |

Twin block |

2.07 |

2.74366 |

-18.124 |

0 |

| CFJC |

20.55 |

4.86428 |

| Pogonion |

Twin block |

17.1967 |

11.3336 |

-3.278 |

0.002 |

| CFJC |

25.2367 |

7.21165 |

When CBCT parameters were compared between the two groups, statistically significant differences were observed in mean values for condylar position, condylar height, and anterior joint space (Table 3) in the CFJC group. Table 4 shows that statistically significant differences were found in the intergroup comparison of parameters assessing patient comfort and perception of the appliance, indicating better compliance with the CFJC appliance (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of CBCT parameters between twin block and CFJC group

|

Parameter

|

Groups

|

Mean

|

Standard Deviation

|

t

-value

|

P

value

|

| Condylar position |

Twin block |

0.3623 |

1.03777 |

-2.731 |

0.008 |

| CFJC |

0.9850 |

0.69498 |

| Condylar height |

Twin block |

-0.7900 |

0.67696 |

-11.656 |

0.000 |

| CFJC |

1.2003 |

0.64535 |

| Condylar width |

Twin block |

1.1237 |

1.32515 |

-1.496 |

0.140 |

| CFJC |

1.5317 |

0.68949 |

| Posterior Joint Space |

Twin block |

3.6287 |

25.20830 |

0.489 |

0.627 |

| CFJC |

1.3760 |

0.84388 |

| Anterior Joint Space |

Twin block |

-0.3633 |

0.70156 |

2.554 |

0.013 |

| CFJC |

-1.0320 |

1.25084 |

| Superior condylar space |

Twin block |

-1.1190 |

0.61598 |

1.366 |

0.177 |

| CFJC |

1.3960 |

0.74388 |

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of patient comfort and perception between twin block and CFJC group

|

Parameter

|

Groups

|

Mean

|

Standard Deviation

|

t

-value

|

P

value

|

| Pain perception |

Twin block |

6.3167 |

0.82507 |

11.250 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

4.0833 |

0.70812 |

| Patient Comfort |

Twin block |

6.5167 |

0.51668 |

-2.614 |

0.011 |

| CFJC appliance |

6.9500 |

0.74683 |

| Appliance appeal/ appearance |

Twin block |

5.3667 |

0.65566 |

-11.843 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

7.3900 |

0.66765 |

| Complexity of regimen |

Twin block |

5.4333 |

0.69149 |

-5.705 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

6.4333 |

0.66609 |

| Cost |

Twin block |

5.5167 |

0.59427 |

-6.517 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

6.5167 |

0.59427 |

| Maintenance of oral hygiene and appliance |

Twin block |

5.4167 |

0.64438 |

-6.010 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

6.4167 |

0.64438 |

| Visibility of appliance in the mouth |

Twin block |

5.5500 |

0.53094 |

13.604 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

3.6000 |

0.57834 |

| Confidence |

Twin block |

5.4667 |

0.58624 |

-6.606 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

6.4667 |

0.58624 |

| Patient perceived values for appliance |

Twin block |

5.5700 |

0.52729 |

-14.690 |

0.000 |

| CFJC appliance |

7.5700 |

0.52729 |

| Speech related problems |

Twin Block |

6.3367 |

0.72420 |

10.696 |

.000 |

| CFJC Appliance |

4.3367 |

0.72420 |

Discussion

Class II malocclusion is prevalent among Indian populations, with rates ranging from 10% to 25%.19 Factors such as genetics, cultural practices, and environment influence these rates, alongside variations in diagnostic criteria and study methodologies. A higher prevalence of Class II malocclusion in boys compared to girls has been noted, highlighting a gender predilection.20 Early detection and appropriate orthodontic intervention are crucial in managing this significant dental issue in India. The optimal timing for myofunctional therapy initiation is debated, but studies suggest it is most effective during stages 3 to 4 of cervical vertebrae maturation (around or just after puberty).21,22 This study includes ages 10‒15 years for both genders, aligning with Tanner and colleagues’ findings of peak height velocity at approximately 12 years in girls and 14 years in boys.23

In both groups, post-treatment changes in SNA were notable (P < 0.05). Group T showed a significantly greater increase in SNA compared to group C. O’Brien et al5 observed a nominal restraining effect on maxillary growth with the twin block appliance, constituting 13% of skeletal changes, while Illing et al24 reported a slight mean reduction in SNA. The forward positioning of the mandible can create a reciprocal restraining effect on the maxilla, known as the headgear effect,25,26 influencing maxillary growth differently in various studies.27-31 Maxillary position relative to the cranial base did not significantly change post-treatment in either group.

This study showed that the decrease in ANB angle following twin block appliance therapy could result from a reduction in SNA, an increase in SNB, or both. Toth and McNamara31 reported a 1.8˚ decrease in ANB angle with twin block treatment, similar to findings by Illing et al.24 Our study also showed a significant mean reduction in ANB angle. Significant differences (P < 0.001) were found in N-perpendicular-to-pogonion values between the groups, indicating forward spatial changes due to mandibular anterior positioning. These results align with previous studies by O’Brien et al5 and Singh et al,22 affirming the efficacy of twin block therapy for correcting skeletal Class II malocclusions.

The upper incisors showed reduced inclination, possibly due to a headgear-like effect from the inclined blocks. In contrast, lower incisors inclined more towards the cranial base, which was influenced by forward mandibular positioning. This contributed to decreased overjet. Studies by Clark32 and Illing et al24 demonstrated significant effects on maxillary incisor inclination with twin block therapy, emphasizing dentoalveolar correction over mandibular growth. Both study groups showed significant mandibular length increases (P < 0.001), with comparable skeletal effects between appliances and minor dental differences, as supported by previous research.24,33

The soft tissue cephalometric analysis serves as a critical method for both vertical and horizontal profile assessment, extending the principles outlined in “Facial Keys to Orthodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Planning” by Arnett.34 Quintão et al35 noted significant upper lip changes due to maxillary incisor retroclination post-functional appliance treatment, contrasting with Morris and colleagues’36 findings of no significant sagittal upper lip change despite reduced overjet. In our study, both appliance groups showed decreased upper lip projection. Lower lip changes were significant in both groups, with greater advancement observed in the CFJC appliance group. Nasolabial angle changes were not significant, consistent with recent meta-analyses.37

The present study evaluated condylar position changes after treatment with twin block and CFJC appliances. CFJC group showed more significant shifts, consistent with prior research by Arumugam et al38 Condylar movements included anterior shifts, akin to findings with Herbst appliances,39 twin block,40-42 and other functional appliances.43 Condylar height increased notably in both groups, contrasting with decreased heights in untreated controls.44 Condylar width increased, more so in CFJC, aligning with findings by Parvathy et al.45 Condyle growth in functional therapy enhances mandibular length and volume,45,46 promoting sagittal and vertical condylar dimensions. TMJ changes noted anterior and posterior joint space adjustments after treatment, similar to findings by Yildirim et al47 and Bayram et al.48 Functional appliances influence articular fossa growth, aiding mandibular repositioning.49 Despite challenges in assessing fossa remodeling, TMJ space alterations indicate treatment efficacy. The study’s comprehensive analysis supports CFJC’s superiority in achieving favorable skeletal, dental, and soft tissue outcomes in Class II malocclusion over twin block within a 12-month treatment period.

Patient compliance and satisfaction were assessed for twin block and CFJC appliances based on pain perception, comfort, appearance, regimen complexity, cost, hygiene, visibility, confidence, and speech issues. Both groups showed significant differences. Twin block was associated with higher pain perception, visibility, and speech-related problems, while CFJC was associated with comfort, appearance, regimen simplicity, cost-effectiveness, patient confidence, and perceived appliance value. Similar findings in patient satisfaction were reported by Golfeshan et al,50 highlighting reduced speech issues with clear aligners. Oliver and Knapman’s study51 and Thirumurthi and colleagues’52 psychological assessments also underscored patient satisfaction and challenges associated with orthodontic treatment, aligning with our study’s outcomes.

Conclusion

This prospective clinical study aimed to evaluate condylar position changes using CBCT in treating Class II malocclusion with the twin block and CFJC appliances. Key findings include:

-

Both appliances significantly improved skeletal, dental, and soft tissue parameters post-treatment.

-

The CFJC appliance yielded superior skeletal, dental, and soft tissue changes compared to the traditional twin block.

-

TMJ changes were observed in both groups, with the CFJC group exhibiting more pronounced changes than the twin block group.

-

CFJC showed enhanced efficacy due to more significant condylar remodeling compared to the twin block appliance.

-

Patient compliance was higher in the CFJC group, possibly due to reduced treatment duration compared to traditional twin block therapy.

These results highlight that the CFJC appliance emerges as a preferred treatment for Class II malocclusion, demonstrating superior efficacy in enhancing skeletal, dental, and soft tissue changes, as well as promoting condylar remodeling and improved patient compliance.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests related to the publication of this work.

Ethical Approval

This study received ethical approval from institutional review board (PIMS/DR/PhD/RDC/2022/134).

References

- Mohamed RN, Basha S, Al-Thomali Y. Changes in upper airway dimensions following orthodontic treatment of skeletal class II malocclusion with twin-block appliance: a systematic review. Turk J Orthod 2020; 33(1):59-64. doi: 10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2020.19028 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gurudatta NS, Kamble RH, Sangtani JK, John ZA, Ahuja MM, Khakhar PG. Discomfort, expectations and experiences during treatment of class II malocclusion with clear block and twin-block appliance-a pilot survey. J Evol Med Dent Sci 2021; 10(15):1064-8. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2021/227 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ehsani S, Nebbe B, Normando D, Lagravere MO, Flores-Mir C. Short-term treatment effects produced by the twin-block appliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 2015; 37(2):170-6. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju030 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Appelbe P, Davies L, Connolly I. Early treatment for class II division 1 malocclusion with the twin-block appliance: a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 135(5):573-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.042 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Sanjie Y, Mandall N, Chadwick S, et al. Effectiveness of early orthodontic treatment with the twin-block appliance: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Part 1: dental and skeletal effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;124(3):234- 43; quiz 339. 10.1016/s0889540603003524.

- Read MJ, Deacon S, O’Brien K. A prospective cohort study of a clip-on fixed functional appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004; 125(4):444-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.05.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Behroozian A, Kalman L. Clear Twin Block: A Step Forward in Functional Appliances. Dental Hypotheses 2020; 11(3):91-4. doi: 10.4103/denthyp.denthyp_14_20 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pavoni C, Lione R, Lugli L, Loberto S, Cozza P. Treatment timing considerations for mandibular advancement with clear aligners in skeletal class II malocclusions. J Clin Orthod 2022; 56(8):464-71. [ Google Scholar]

- Daokar S, Sharma M. A systematic review of skeletal, dental and soft tissue treatment effects of twin-block appliance. Orthod J Nepal 2020; 10(1):65-72. [ Google Scholar]

- Sidlauskas A. Clinical effectiveness of the twin-block appliance in the treatment of class II division 1 malocclusion. Stomatologija 2005; 7(1):7-10. [ Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Xia W, Yang K, Li X, Zhang F, Xu J. The efficacy of twin-block appliances for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2022; 2022:3594162. doi: 10.1155/2022/3594162 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiang YY, Sun L, Wang H, Zhao CY, Zhang WB. Three-dimensional cone beam computed tomography analysis of temporomandibular joint response to the twin-block functional appliance. Korean J Orthod 2020; 50(2):86-97. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2020.50.2.86 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alfakhouri A, Al-Sabbagh R, Jabbour O. Skeletal effect of modified twin-block with clear plates versus conventional twin-block in class II malocclusions-a randomized controlled trial of functional appliances Biomedical Science and Clinical Research. 2023 S ep 9; 2(3):313-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Zhang Y, Wu Q, Xiao H, Li F. Three-dimensional spatial analysis of the temporomandibular joint in adult patients with class II division 2 malocclusion before and after orthodontic treatment: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2023; 23(1):477. doi: 10.1186/s12903-023-03210-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Saleh MA, Alsufyani N, Flores-Mir C, Nebbe B, Major PW. Changes in temporomandibular joint morphology in class II patients treated with fixed mandibular repositioning and evaluated through 3D imaging: a systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res 2015; 18(4):185-201. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12099 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zheng J, Wu Q, Jiang T, Xiao H, Du Y. Three-dimensional spatial analysis of temporomandibular joint in adolescent class II division 1 malocclusion patients: comparison of twin-block and clear functional aligner. Head Face Med 2024; 20(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13005-023-00404-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- He J, Hu L, Yuan Y, Wang P, Zheng F, Jiang H. Comparison between clear aligners and twin-block in treating class II malocclusion in children: a retrospective study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2024; 48(5):125-30. doi: 10.22514/jocpd.2023.070 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lombardo EC, Lione R, Franchi L, Gaffuri F, Maspero C, Cozza P. Dentoskeletal effects of clear aligner vs twin block-a short-term study of functional appliances. J Orofac Orthop 2024; 85(5):317-26. doi: 10.1007/s00056-022-00443-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Balachandran P, Janakiram C. Prevalence of malocclusion among 8-15 years old children, India - a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2021; 11(2):192-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.01.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Siddegowda R, Satish RM. The prevalence of malocclusion and its gender distribution among Indian school children: an epidemiological survey. SRM J Res Dent Sci 2014; 5(4):224-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Baccetti T, Franchi L, Toth LR, McNamara JA Jr. Treatment timing for twin-block therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 118(2):159-70. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.105571 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Singh M, Saini A, Misra V, Sharma VP, Singh GK. Timing of myofunctional appliance therapy. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2010; 35(2):233-40. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.35.2.9572h13218806871 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Marubini E, Resele LF. The adolescent growth spurt of boys and girls of the Harpenden growth study. Ann Hum Biol 1976; 3(2):109-26. doi: 10.1080/03014467600001231 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Illing HM, Morris DO, Lee RT. A prospective evaluation of bass, bionator and twin-block appliances Part I--the hard tissues. Eur J Orthod 1998; 20(5):501-16. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.5.501 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM. Contemporary Orthodontics. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, Elsevier; 2007.

- Jena AK, Duggal R, Parkash H. Skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of twin-block and bionator appliances in the treatment of class II malocclusion: a comparative study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006; 130(5):594-602. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.02.025 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kerr WJ, TenHave TR, McNamara JA Jr. A comparison of skeletal and dental changes produced by function regulators (FR-2 and FR-3). Eur J Orthod 1989; 11(3):235-42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejo.a035991 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pancherz H. Treatment of class II malocclusions by jumping the bite with the Herbst appliance A cephalometric investigation. Am J Orthod 1979; 76(4):423-42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(79)90227-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Perillo L, Johnston LE Jr, Ferro A. Permanence of skeletal changes after function regulator (FR-2) treatment of patients with retrusive class II malocclusions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996; 109(2):132-9. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70173-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SD, Sinclair PM, Hamilton RH. A cephalometric, tomographic, and dental cast evaluation of Fränkel therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1987; 92(5):427-36. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90264-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Toth LR, McNamara JA Jr. Treatment effects produced by the twin-block appliance and the FR-2 appliance of Fränkel compared with an untreated class II sample. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1999; 116(6):597-609. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70193-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Clark WJ. The twin-block technique A functional orthopedic appliance system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988; 93(1):1-18. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90188-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lund DI, Sandler PJ. The effects of twin blocks: a prospective controlled study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998; 113(1):104-10. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70282-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arnett GW, Bergman RT. Facial keys to orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning Part I. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1993; 103(4):299-312. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(93)70010-l [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Quintão C, Helena I, Brunharo VP, Menezes RC, Almeida MA. Soft tissue facial profile changes following functional appliance therapy. Eur J Orthod 2006; 28(1):35-41. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji067 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Morris DO, Illing HM, Lee RT. A prospective evaluation of bass, bionator and twin-block appliances Part II--the soft tissues. Eur J Orthod 1998; 20(6):663-84. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.6.663 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Fang Y, Sui X, Yao Y. Comparison of twin-block appliance and Herbst appliance in the treatment of class II malocclusion among children: a meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024; 24(1):278. doi: 10.1186/s12903-024-04027-w [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arumugam S, Sathyanarayana HP, Padmanabhan S. Temporomandibular joint and skeletal changes in response to twin-block and AdvanSync appliance therapy–a three-dimensional study. APOS Trends Orthod 2023; 13(4):197-204. doi: 10.25259/apos_39_2023 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cheib PL, Cevidanes LHS, de Oliveira Ruellas AC, Franchi L, Braga WF, Oliveira D. Displacement of the mandibular condyles immediately after Herbst appliance insertion - 3D assessment. Turk J Orthod 2016; 29(2):31-7. doi: 10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2016.160008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Elfeky HY, Fayed MS, Alhammadi MS, Soliman SA, El Boghdadi DM. Three-dimensional skeletal, dentoalveolar and temporomandibular joint changes produced by twin-block functional appliance. J Orofac Orthop 2018; 79(4):245-58. doi: 10.1007/s00056-018-0137-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiang YY, Sun L, Wang H, Zhao CY, Zhang WB. Three-dimensional cone beam computed tomography analysis of temporomandibular joint response to the twin-block functional appliance. Korean J Orthod 2020; 50(2):86-97. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2020.50.2.86 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chavan SJ, Bhad WA, Doshi UH. Comparison of temporomandibular joint changes in twin-block and bionator appliance therapy: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Prog Orthod 2014; 15(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s40510-014-0057-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chintakanon K, Sampson W, Wilkinson T, Townsend G. A prospective study of twin-block appliance therapy assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 118(5):494-504. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.109839 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Parvathy RM, Shetty S, Katheesa P. Evaluation of changes seen in TMJ after mandibular advancement in treatment of class II malocclusions, with functional appliances, a CBCT study. Biomedicine 2021; 41(2):236-42. [ Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Schneider P, Matthews H, Roberts WE, Xu T, Wei R. 3D assessment of mandibular skeletal effects produced by the Herbst appliance. BMC Oral Health 2020; 20(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01108-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wei RY, Atresh A, Ruellas A, Cevidanes LH, Nguyen T, Larson BE, et al. Three-dimensional condylar changes from Herbst appliance and multibracket treatment: a comparison with matched class II elastics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2020;158(4):505-17.e6. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.09.011.

- Yildirim E, Karacay S, Erkan M. Condylar response to functional therapy with twin-block as shown by cone-beam computed tomography. Angle Orthod 2014; 84(6):1018-25. doi: 10.2319/112713-869.1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bayram M, Kayipmaz S, Sezgin OS, Küçük M. Volumetric analysis of the mandibular condyle using cone beam computed tomography. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81(8):1812-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.04.070 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ruf S, Baltromejus S, Pancherz H. Effective condylar growth and chin position changes in activator treatment: a cephalometric roentgenographic study. Angle Orthod 2001; 71(1):4-11. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0004:Ecgacp>2.0.Co;2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Golfeshan F, Soltani MK, Zohrei A, Poorolajal J. Comparison between classic twin-block and a modified clear twin-block in class II, division 1 malocclusions: a randomized clinical trial. J Contemp Dent Pract 2018; 19(12):1455-62. [ Google Scholar]

- Oliver RG, Knapman YM. Attitudes to orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthod 1985; 12(4):179-88. doi: 10.1179/bjo.12.4.179 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thirumurthi AS, Felicita AS, Jain RK. Patient’s psychological response to twin-block therapy. World J Dent 2017; 8(4):327-0. [ Google Scholar]